Fermi Friday - August 24, 2018

Fermi Talks Tech: The Rapid Response World of Gamma-ray Bursts

Posted by: Judy Racusin (NASA/GSFC)

The distinct signatures of a bright burst of gamma-rays lasting from a fraction of second up to minutes and then fading away forever is the telltale sign of gamma-ray bursts (GRBs). This behavior makes them rather unusual in astronomy, because they require automated science pipelines to detect, localize, and characterize new transients, then distribute information about them to the worldwide community within seconds. Scientists need to be on call and respond immediately to new events in order to catch the slower fading afterglow emission in radio, optical, X-ray and high-energy gamma-rays. On Fermi, this work is supported by ~10 scientists on the Gamma-ray Burst Monitor (GBM) team and ~20 scientists on the Large Area Telescope (LAT) Team.

Whenever a GRB is detected by the GBM (2-3 times per week), a series of events transpire automatically, alerting sky-watchers to take a closer look. Onboard, the GBM computer constantly scans the data from all 14 detectors looking for sudden increases in the rate of gamma rays. When it finds one of these, it produces a trigger, and checks if it's consistent with any known sources like the Sun. That trigger starts another series of events including finding the localization of the source and sending down the data in a window from 30 seconds before the trigger to several minutes afterwards. LAT can also trigger onboard, though these are very rare, after which a similar list of photons and initial localization are sent to the ground.

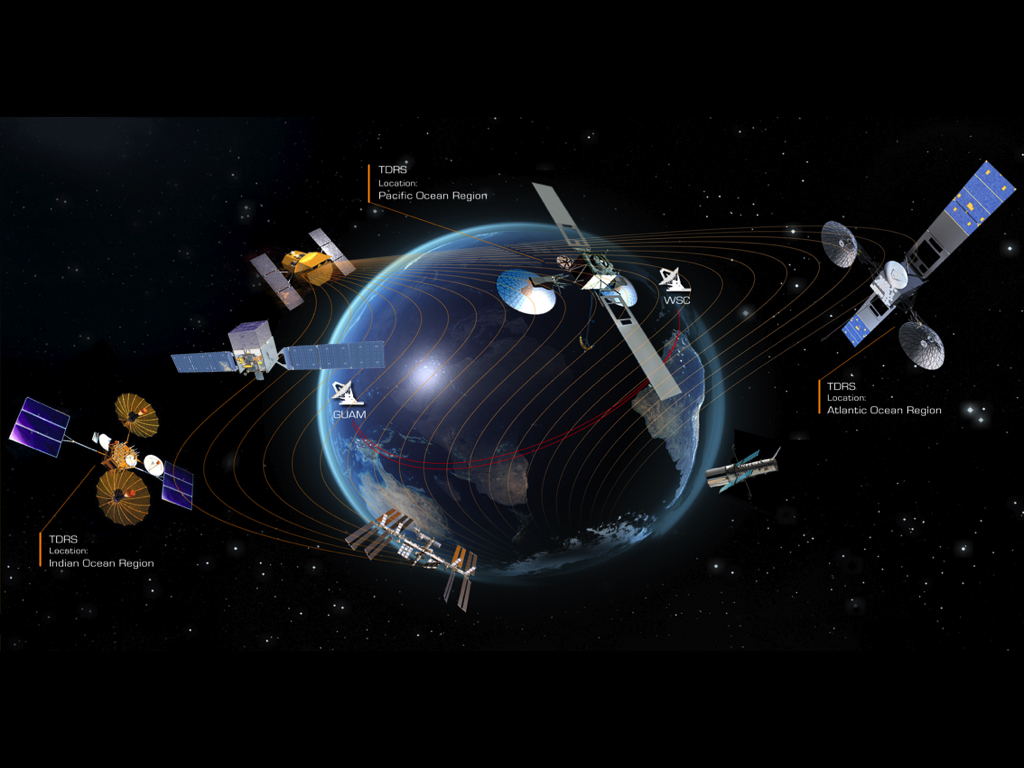

Fermi utilizes a communication platform known as the Tracking Data Relay Satellite (TDRS) system. This network of NASA communications satellites allows Fermi to send down small snippets of data within seconds at any time, and also our full larger datasets using a higher bandwidth antenna at pre-scheduled intervals every couple of hours.

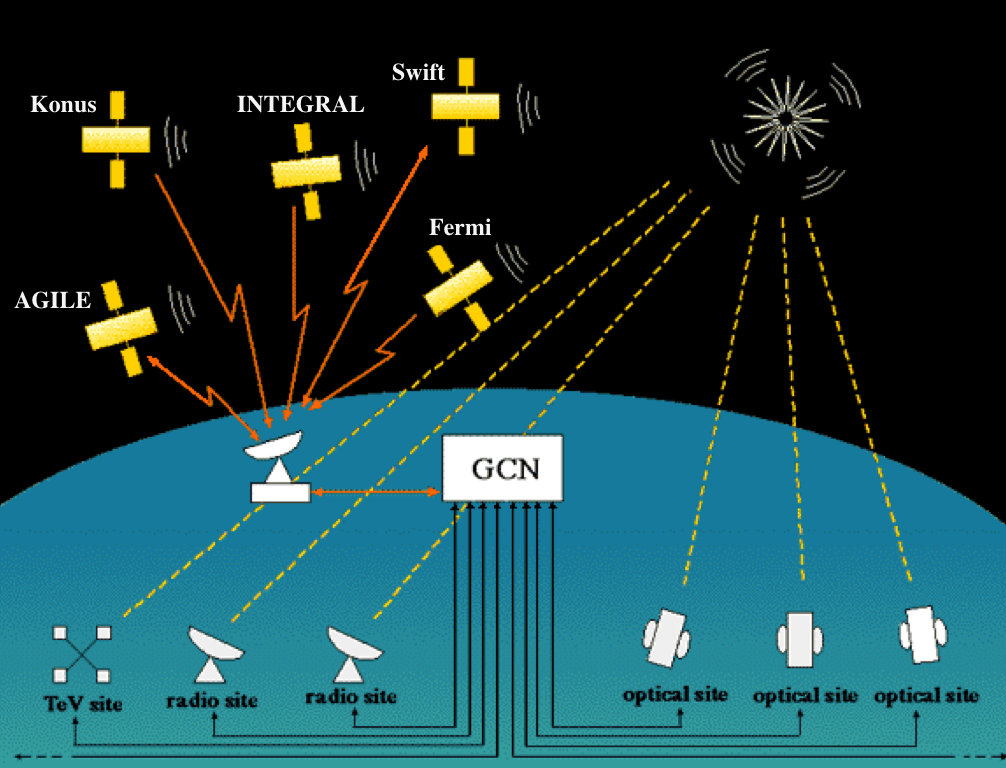

The trigger data are ingested by dedicated computer pipelines for both the GBM and the LAT. These are constantly running in real time collecting the data that comes from Fermi, doing additional analysis, and distributing alerts and data products to the community.

The GRB community has been efficiently jumping into action since the 1990's, thanks to a system known as the Gamma-ray Coordinates Network (GCN). GCN was initially developed for the Burst And Transient Search Experiment (BATSE) on the Compton Gamma-ray Observatory and has become the clearing house for all GRB missions since. GCN receives automated notifications from satellites and distributes them to astronomers. It also has another communication path that allows astronomers to report on their findings and coordinate follow-up observations.

We take shifts, where at any random moment we get text messages and emails alerting us to the detection of a new GRB. That means we have to spring into action. We quickly get to our computers (or smartphones) and look at the initial data, call into a telecon or join a group chat, and determine if the source is really a GRB, if it's interesting, and if so to alert the community that they should follow it up with telescopes all over the world to learn as much as we can before it fades away forever.